In the age of social entrepreneurship, underserved consumer minorities are finally sharing the spotlight. As per the WHO, World Health Organisation, 1 in 6 people are differently abled – while these 15% have long since sounded the cry for universally designed clothing, there is a fair share of the global population that is unaware of what adaptive fashion means or to whom it caters. For brands under social and peer pressure to improve their inclusivity narrative adaptive fashion is simply an opportunity. But for differently abled people, it is now becoming a long due reality.

Certain brands embraced the need to cater to disabled individuals a few years ago by designing garments and accessories for people with mobility and sensory issues. One of the most internationally lauded names is Tommy Hilfiger, whose Adaptive line released in 2017. The garments featured magnetic buttons, adjustable waistbands and more. Nike’s accessibly designed footwear capsule FlyEase, launched in early 2021, inspired by a letter from a teenager with cerebral palsy. After several design iterations over the years the sneakers now feature a wraparound zipper and larger opening for hands-free fitting. Last September, during NYFW SS’24, Victoria’s Secret debuted an adaptive intimates line with accessibility features including front-facing adjustable bra straps, magnetic and Velcro closures.

Until recently, these brand initiatives were considered far from ordinary, making them the exception rather than the rule. So, cards on the table, why did it take this long for adaptive fashion to become part of mainstream vocabulary?

When it comes to logistics and production, there are many barriers to entry. Small-scale brands lack skilled workers knowledgeable about designing for disability. Here, limited collaboration between healthcare professionals, designers and manufacturers, is a probable cause. Further, retailers cite low demand and visibility for higher price ranges thus unable to maintain an ethical balance between commercial and social activity. Despite these challenges to growth Forbes reported the market for adaptive fashion is estimated to reach $400bn by 2026. The reason for this positive trajectory is far from optimistic. According to the World Health Organization, (WHO), there are currently over 1 billion disabled people in the world and this figure is projected to increase due to growing aging populations and chronic diseases borne of environmental and lifestyle factors.

On the flipside, reducing stigma surrounding disability is responsible for the rapidly closing gap between supply and demand in adaptive fashion. Shay Senior, founder of AI-powered inclusive fashion search engine, Palta, is propagating the idea that adaptive fashion needn’t be limited to a target market of differently abled consumers but rather thought of as universal and inclusive design. Citing an example Senior says that a pair of trousers, designed for a wheelchair user, could be extended towards individuals who maintain a seated posture for many hours of the day. Also, magnetic closures ease the process of dressing for people with dexterity issues but their sleek style may appeal to many others. By breaking the taboo on disability, he cultivates the belief that adaptive clothing is for the masses: “Too often brands worry that designing an adaptive collection would be a complete departure from what they currently do and that they would need new factories and fabrics. But in reality, it isn’t that black and white and the markets are far more interconnected than they imagine.”

In Contrast, Carol Taylor, designer and co-founder of the Australian brand Christina Stephens, lends insight into what goes into the making of adaptive fashion. Speaking from experience, as a quadriplegic, Taylor is of the opinion that good adaptive design doesn’t stop at magnetic fastenings. She shares, “When designing for someone in a wheelchair it’s not just about the seated position, there’s so much more to be considered. A seam placed in the wrong position can cause a pressure injury or too much fabric in the wrong spot can cause nerve pain.”

Rather than deep dive into the nuances of such design most brands do just enough to tease the conscious consumer about their inclusive collections. But it is often the social entrepreneurs who hit the nail on the head by addressing the needs of specific communities. Asiya Rafiq launched Adaptive by Asiya to create modest clothing for disabled Muslim women and Indian labels, by Nidhi Munim and Shivan & Narresh, created mastectomy swimwear and blouses. Zyenika offers trousers with kneepads for adults who move by crawling. Whether under the umbrella of tokenism or a virtuous championing of social causes many home-grown and small scale labels have cropped up over recent years with more holistic adaptive offerings. Social Surge, Unhidden, I Am Denim, So Yes, Cur8ability, Aaraam Se are a few examples.

Kudos to this emerging pool of talent but it’s not enough to design clothing for disabled people; accessibility to purchase and visibility to discover are also important factors to consider. In this regard UK-based e-commerce platform, Adaptista, is positioning itself as a cornerstone for inspiration. Launched in 2022, by Maria O’Sullivan, it offers a curated selection of adaptive clothing brands and is ‘custom built and tested by disabled software development experts.’ Adaptista partners with Recite Me, a software based accessibility tool with options such as text-to-speech, speech recognition, magnification and text styling.

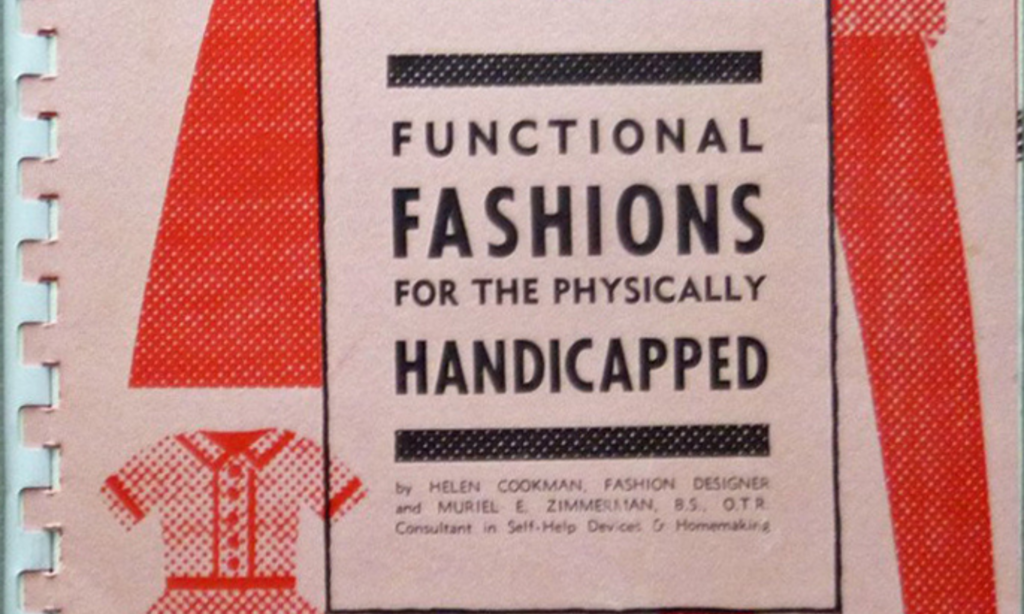

Although the recent forays into adaptive fashion and representation may seem to be taking hold more widely it was actually the designer, Helen Cookman, who brought international recognition for the need for such clothing in the 1950s. Her debut capsule collection, ‘Functional Fashions,’ was created with the aim to help World War II injured soldiers, veterans with physical disabilities and people affected by polio. The 17 piece capsule was a result of her collaboration with physician, Howard Rusk, at the Institute for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in 1948. Cookman’s designs included blouse pleats, double-fabric under arms, to withstand pressure from crutches, Velcro fastenings and sewn into garment hearing aid pouches. By the 1960s, Cookman’s designs were commercially recognised and she collaborated with brands such as Levi’s, Lacoste and Sears among others.

Today, celebrating disability in fashion extends from smart clothing to inclusive representation. Model, Danielle Sheypuk, was the first to roll down the NYFW runway in a wheelchair in 2014 and since then many models have mustered the courage to follow suit. Sofia Jirau and Ellie Goldstein are both models with Down Syndrome. Amiee Mullins is an amputee and Aaron Rose Philip, born with quadriplegic cerebral palsy, was the first Black, transgender model to be represented by a major modelling agency.

Enabling such representation in the fashion industry is The Runway of Dreams Foundation, founded by Mindy Scheier in 2014. The Foundation has been hosting shows at NYFW and LAFW with disabled models for years with the most recent show held during NYFW SS’24. It featured 70 disabled models wearing adaptive collections from brands such as Zappos, Steve Madden, Tommy Hilfiger, Target, Victoria’s Secret and PINK. Participating model Jay Manuel shared, “A night like this with so much representation is important because we don’t get to see it in our daily lives, so it shows that you’re not alone and that there’s a community in the disability space and we’re able to be fashionable too.

With such positive reinforcements in recent years it begs the question: when did we stop designing for functionality?

Photos courtesy of Mighty Well, Intimately, IMAXTree for Genentech, The Chipstone Foundation, The Milwaukee Art Museum and Richie Keo-Setbon.